Why Copper Shortages Point to Photonics (Not Just Battery Tech)

The InP Integration Layer and the Future of Lattice-Matched Stacks

Why Copper Shortages Point to Photonics (Not Just Battery Tech)

Global copper demand is projected to outstrip supply starting 2027, with deficits extending through 2040. The math is straightforward: electrification (EVs, renewable infrastructure, data centers) is consuming copper faster than new mines can spin up.

The Wellness Problem: The Materials Crunch

As we push toward a fully electrified and AI-integrated future, we are hitting a physical wall. The "Wellness Problem" here isn't just about resource scarcity; it's about the systemic anxiety of building a civilization on a disappearing foundation. We are trying to scale digital infinite growth on a finite, heavy-metal substrate. This creates a friction point where the cost of moving data and energy starts to exceed the value created.

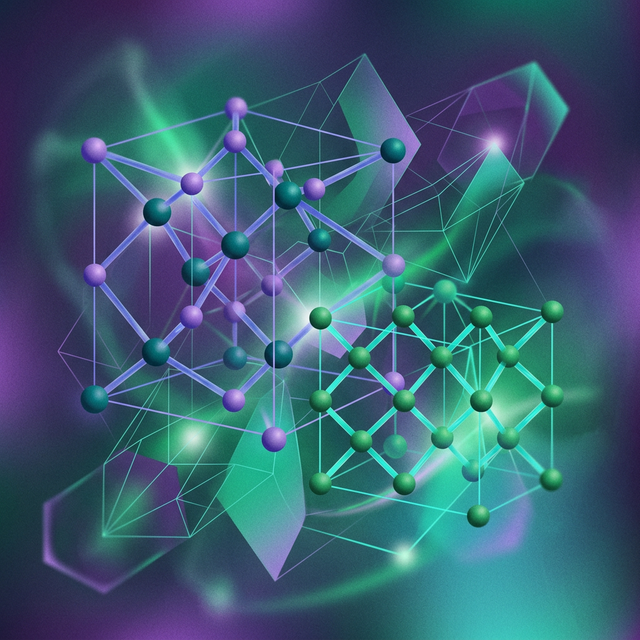

The Root Cause: Lattice Incompatibility

Silicon dominated for decades not because it's theoretically optimal, but because we built an entire manufacturing ecosystem around its 5.431 Å lattice constant. But silicon has physical limits: heat, speed, and energy efficiency.

The next architecture—photonics (computing with light)—requires different materials with different atomic structures. The reason we haven't seen a massive swap is because of the "Integration Problem." You can't just swap silicon for light-based chips without creating "threading dislocations"—atomic-level cracks that ruin performance. The root cause of our tech bottleneck is a fundamental material mismatch.

The CSD Resolution: The Integration Layer (InP)

In Conscious Stack Design™, we teach that the constraint is the design. Indium Phosphide (InP), with a lattice constant of 5.864 Å, is the material that solves the integration problem. It is the "buffer layer" that allows photonic components to talk to silicon systems without breaking.

In my stack methodology:

- Your Anchor tool (using the 5:3:1 protocol) is like Indium Phosphide. It defines the "lattice constant" your entire stack must respect.

- Tools that don't lattice-match create the digital equivalent of threading dislocations: broken automations, context-switching friction, and manual data re-entry.

- The Nickel Pivot is a signal that we must rethink our materials from the ground up—both in hardware and in our personal technology stacks.

The companies and operators who dominate the next decade won't just build faster pipes; they'll build compatible faster pipes. Indium Phosphide for hardware integration, and CSD for cognitive integration.

What I'm Watching

- Fabrication Bottlenecks: Smart Photonics (Netherlands) is scaling InP production.

- Geopolitical Pressure: Indium is a byproduct of zinc mining, making it a critical strategic material.

- Crypto-Provenance: Moving petabytes per second через AI pipelines requires blockchain-based auditability to prevent a liability time bomb.

Open this article in your preferred AI assistant — or highlight text first for focused analysis.

If this transmission landed, you can support the work.